Rolex and Golf

More Than Time

By Tony TrainaMay 05, 2021Photo Courtesy of USGAIf I'm being honest, it's probably my first memory of the name. Rolex. Before I even knew what it meant, it was the goal. First on the golf course, and then, off it too.

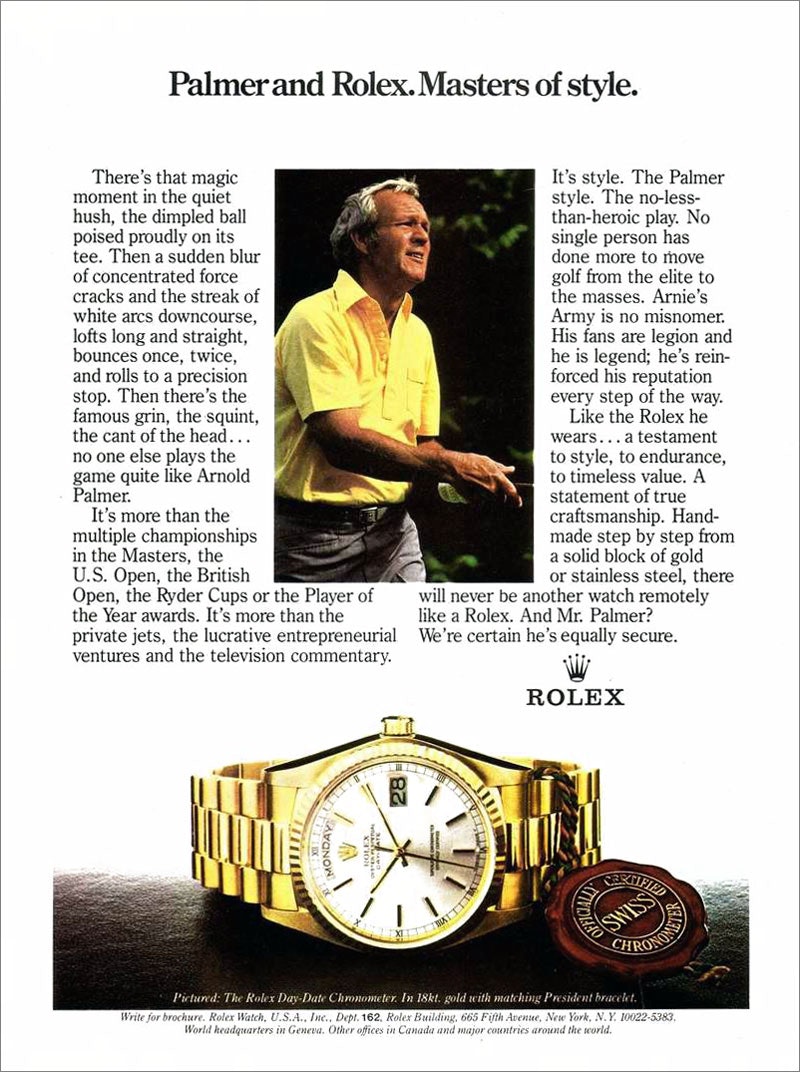

If you ask Rolex, its relationship with golf started on the wrist of Arnold Palmer in 1967. The King, wearing the Crown. Soon, he was joined in Rolex's ambassador lineup by Gary Player and Jack Nicklaus. The Big Three.

For me, it started around 40 years later, sometime around 2007.

When you’re a junior golfer, playing in the American Junior Golf Association (AJGA) Rolex Tournament of Champions is a primary objective each summer. It’s the preeminent end-of-season tournament on the preeminent junior golf tour, all brought to you by Rolex. If you’re really good, you might even be named to the Rolex Junior All-America Team.

Each summer, young golfers with Tiger headcovers and too many artificial fabrics tee it up with the dream of qualifying for the Rolex Tournament of Champions or being named to the Rolex Junior All-America Team. With names like Tiger and Phil scrawled on the tournament’s trophy —small hints of legendary careers to come— it’s a chance to etch your name in the annals of history, or at least in its junior golf footnotes.

After bringing Mr. Palmer on board in 1967, Rolex went on to forge a deep relationship with golf. Not only with ambassadors like Nicklaus and Player, but by sponsoring (nay, becoming the “official timekeeper” of) The Masters, U.S. Open, The Open Championship, and PGA Championship, all four of the men’s majors.

The brand, previously associated with daring sports like diving and driving, with achievements like summiting Everest and swimming across the English Channel, forged a relationship with a supposedly more debonair pursuit reserved as a leisurely endeavor for the elite.

In a sport that begins with tee times, where Young Tom Morris won his first Open Championship in the same year (1868) that Patek Philippe introduced the first wristwatch, it’s a partnership that was always meant to be.

But the golf of 1967 wasn’t that same debonair sport that Young Tom Morris dominated a century prior while wearing knickers and swinging hickory shafts around the country club. By then, it was Arnold Palmer striding down the fairway with a screaming gallery at his back, smoking darts on the tee box, and generally making the game cooler and more popular than it had ever been. (“When I see some of the old film clips and see how silly I am with that thing hanging out of my mouth…I could just cringe,” Palmer later told Golf Digest of his smoking habit that he eventually kicked.)

Perhaps Rolex saw a bit of itself in golf. A sport rooted in tradition, but in dire need of updating its polos and pleats. After all, Rolex did the same thing with wristwatches: before Rolex came along, wristwatches were these delicate little things worn by the upper class like the fragile pieces of jewelry they were.

Then Rolex came along with the audacity to think that wristwatches could be cool, sporty even. Rolex strapped one onto Mercedes Gleitze when she swam across the English Channel, just to prove that finally, a wearable, waterproof watch had been made.

Golf in 1967 was similarly stuck in its ways, unsure how to move into the modern era. Until Arnold Palmer came along to show that all it took was a relatable guy from working class Pennsylvania who knew how to engage a gallery. Good looks and impeccable style didn’t hurt either.

Arnold Palmer’s personal Rolex Day-Date, engraved ADP on the case back. Courtesy of Heritage Auctions. A guy that we comfortably refer to as both the familiar Arnie and reverent Mr. Palmer in equally endearing ways, and who actually lived up to both titles. He was athletic, but elegant —respectful of the game’s traditions, but not stuck in them.

So like with Mercedes Gleitze, Rolex strapped on for the ride. At their best, golf and Rolex have transformed themselves, and each other, over the proceeding half-century of partnership. Arnie’s Army turned into Tiger’s roars, and more people started paying attention along the way. They sustained each other’s elegance, but in a more accessible, energetic way. No hickory shafts and, well, fewer country clubs.

Soon after sponsoring Mr. Palmer, Rolex began sponsoring tournaments at the junior level too. All with the goal of “supporting the game’s most promising players, even before they become household names,” as Rolex likes to say. It began sponsoring the AJGA Rolex Tournament of Champions in 1978, a premier event in the junior tour’s calendar, eventually going on to sponsor other efforts to expand the game’s global reach at the youth level too.

Jack Nicklaus holding the Claret Jug while wearing his Rolex Day-Date. Photo courtesy of Phillips. Rolex could never just slap its name on some random tour or tournament in rural Indiana that any kid with a little privilege and a lot of dreams could enter. That was the Mountain Dew Junior Tour, thank you very much. And while that junior tour may have temporarily left your correspondent with an on-course addiction to various PepsiCo products (courtesy of coolers full of free drinks on every other tee box), its sponsor didn’t leave the same indelible impression that Rolex did.

Rolex was something to aspire to. Not only did I grow up watching golfers like Phil Mickelson, Annika Sorenstam, and post-2010 Tiger hoist trophies with a Rolex not-so-subtly draped across their wrist, but it was something much more real. A goal, a title, an achievement. More than “Do the Dew.”

Of course, a spot at the Rolex Tournament of Champions or on the Rolex Junior All-America Team was never in the scorecards for me. If you look at the squad from my senior year of high school, with names like Spieth and Thomas headlining (now Rolex ambassadors), I never stood a chance.

Jordan Spieth holding the Claret Jug while wearing a Rolex Explorer II. But that’s okay. While Rolex jumped into golf on the populist movement sparked by Arnold Palmer, for me it remained an aspirational name, perhaps a goal to mark future life achievements.

Listen, in life, we have aspirations. As a young golfer hacking it around, I aspired to becoming a great golfer. Nowadays on the course, it’s to break 80 while not spilling any beer in the cart.

But off the course, we still aspire to great things: relationships, promotions, achievements. Sure, a Rolex might be there to mark one of these. But now, Rolex is just that: the mark, not the goal itself.

That’s what I got wrong as a kid: the goal isn’t Rolex, but what it represents. As a kid, it was travelling to courses and tournaments across the Midwest with siblings, cousins, and friends, all golfers, and making new friends on the course. Heading back to the Holiday Inn after the round and playing euchre in the lobby or sneaking onto the roof to hit a few drivers off it.

No Rolex, no AJGA Rolex Tournament of Champions trophy, can beat that.

So yea, I might’ve kicked that Mountain Dew addiction, but the addictive aspiration for Rolex-worthy achievements still exists. And I might even mark one with a watch.