The Ultimate Sporting Gent's Timepiece

The History of the Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso

By Jared Paul SternMarch 14, 2021When considering the ultimate sports watch it's hard to overlook the importance of the Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso. The now iconic hinged-timepiece —which was created for polo players— has been immortalized in the new book Jaeger-LeCoultre: Reverso, due out on February 1st from French luxury publisher Assouline. The $195 slipcased volume, destined to adorn coffee tables and library shelves the world over, is an opulently-illustrated history of one of watchmaking’s true icons, by British author, historian and tastemaker Nicholas Foulkes, one of the most stylish men in the world.

Using both archival material and newly-commissioned photography, the book traces the horological beginnings of the Reverso prior to its debut in 1931, through its near-extinction and subsequent revival in the mid-1970s, to its eventual immortal position at the pinnacle of fine Swiss watchmaking. While esteemed amongst enthusiasts, the Reverso, the finest example of a hybrid sports-dress watch, is not as well known as the Rolex Submariner or Omega Speedmaster, though in its way the Reverso’s history and evolution are every bit as compelling.

Its origins, Foulkes writes, can be attributed to Swiss-born businessman César de Trey, a distributor of pocket and wristwatches, and a visit he made to British friends in India in 1930, in the latter days of the British Raj—the nearly 90-year period of the British Crown’s rule over India that has inspired everything from Ralph Lauren collections to the way many of us decorate our apartments and houses today. British officers serving in India had popularized the sport of polo there, and de Trey watched more than one match during his visit.

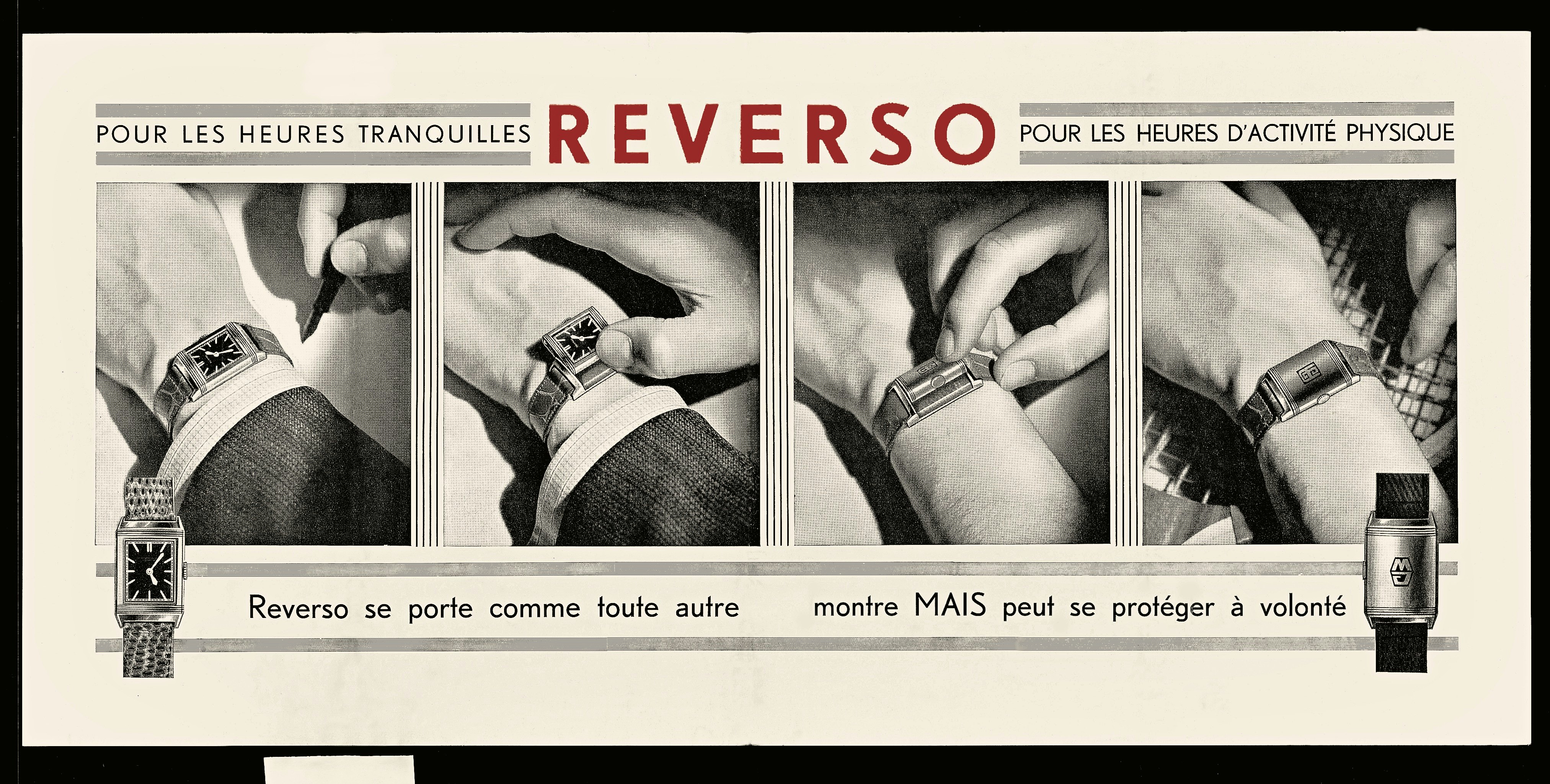

As Manfred Fritz, author of an earlier work on the Reverso (cited by Foulkes) noted, de Trey also observed that the wristwatches “worn by those English sportsmen were regularly among the losers of such matches: although broken watch [crystals] bore silent testimony to the great fighting spirit of their owners, they served only to underline the limited suitability of such timepieces for sporting activities—and, of course, the man of the world would insist on wearing his wristwatch when playing polo, golf or tennis.”

De Trey’s friends among the British officer class “asked him whether it might be possible to make a watch that could be covered or possibly even turned over to protect the fragile glass during the game,” Fritz recounted. “The words ‘turn over' stuck in the mind of their Swiss guest and watch enthusiast like an arrow in its target.” Not long after returning home, in March 1931, de Trey filed a patent application in Paris for “a watch capable of sliding in its support and being completely turned over.” The name Reverso, Latin for “I turn," was registered in November.

To produce this revolutionary new timepiece, de Trey turned to the Swiss branch of Jaeger-LeCoultre, the recent result of a partnership between Edmond Jaeger, notable maker of instruments and dials for aircraft and cars, and the Swiss watchmaker LeCoultre, based in the mountain town of Le Sentier. While the patent application showed a square-dialed timepiece which was “arguably more feminine, more Belle Époque,” Foulkes writes, the first pieces produced under the Reverso name were decidedly more masculine and Art Deco.

All images are courtesy of Assouline. Manufactured entirely in-house at a time when a watche's components were routinely sourced from different firms, and in a way one of the earliest tool watches, “the Reverso’s value lay not in the costliness of its materials and lavishness of its embellishments but in the ingenuity and intricacy of its engineering,” Foulkes notes. Not to give short shrift to its undeniable elegance, and the fact that wearing one made you look like the sort of man who kept a string of polo ponies, or were in any case a man of both action and excellent taste.

One of the Reverso’s early adherents was General Douglas MacArthur, known for his corncob pipe and aviator sunglasses. Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army during the 1930s, he went on to play a decisive role in the Pacific theater during World War II. MacArthur’s personal Reverso, now in Jaeger-LeCoultre’s private collection, was engraved with his monogram on the caseback or reverse face, demonstrating another important feature of the design. “LeCoultre’s promotional materials supplied to retailers extolled the benefits of engraving and enameling,” Foulkes writes, which in addition to initials and monograms extended to coats of arms, club insignia, and even more fanciful designs.

The Reverso’s initial resounding success had begun to wane within 25 years of its debut, however, following the onset of the postwar era and a general turn towards the future in design, culture and aesthetics. By the late-1960s the Reverso was a nearly forgotten relic, and would have remained so if not for the Art Deco revival of the early 1970s, epitomized by the successful release of The Great Gatsby in 1974. Even then it might have languished in the archives, had not an Italian watch distributor insisted there was a new market for the Reverso in that country.

Finally in 1975 a new generation of Reversos, equipped with a new mechanical movement and re-engineered case, entered production—and thrived, despite it being the height of the Swiss watchmaking industry’s “quartz crisis.” Indeed, Foulkes writes, at a time when “many were predicting the very extinction of the mechanical watch” and a large part of the industry as a result, “it is no exaggeration to say that Jaeger-LeCoultre owes its very survival” to the Reverso’s reversal of fortunes.

It was noting short of “one of watchmaking’s miracles,” Foulkes declares: “From the somewhat quixotic beginnings in a distributor’s dogged insistence that there was a taste for the Art Deco icon in early '70s Italy, the Reverso had established itself as a standard bearer of nostalgic elegance.” And it soon earned the status of a design classic, on par with the likes of the Porsche 911.

By the 1980s, it had even re-captured its snob appeal, which it retains to this day, without resorting to the vulgar excesses of many other watches of the era. Its ethos is best summed up by a Reverso advertisement from 1980 unearthed by Foulkes, which reads, “One doesn’t need a watch by Jaeger-LeCoultre just to tell the time—after all, one doesn’t drink a Château Lafite-Rothschild 1947 just to quench a thirst.”